Concept paper- Code of conduct and standard contract_Domestic Workers.docx

Concept Note

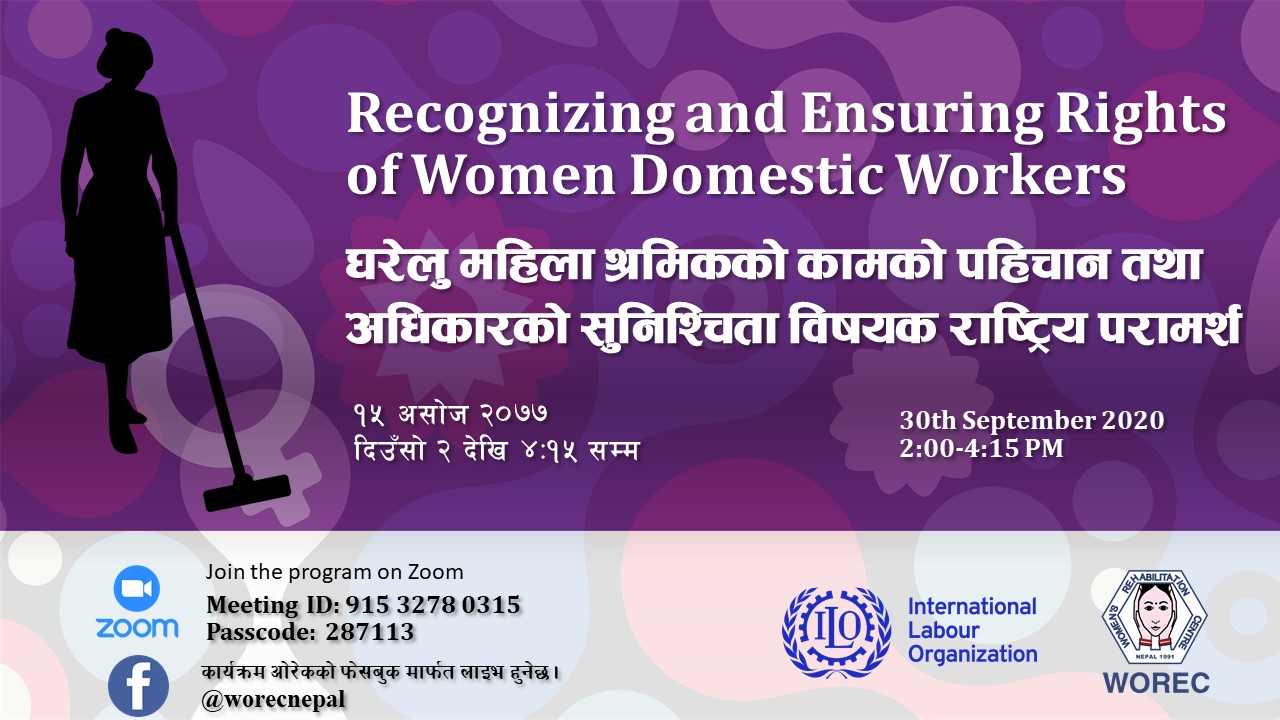

National Consultation program- “Recognizing and Ensuring Rights of Domestic Workers”

Joint initiative of WOREC, ILO, Nepal and Global Fund for Women

Background

As per the ILO Convention 189 the term domestic worker is defined as any person engaged in domestic work with an employment relationship. A person who performs domestic work only occasionally or sporadically and not on an occupational basis is not a domestic worker. Globally, the ILO estimates that there are at least 67 million domestic workers (Excluding child laborers)[1]. Further, 80 percent of the domestic workers are females.[2] A domestic worker can be of various types and nature, some of them may work on full-time or part-time basis; may be employed by a single household or by multiple employers; may be residing in the household of the employer (live-in worker) or may be living in his or her own residence (live-out). Domestic workers predominantly women, comprise one of the most disadvantaged workforces in the world of work. Many of them come from poverty, socially disadvantaged groups and have had limited access to education and are most often vulnerable to physical, sexual, psychological or other forms of abuse, harassment and violence because their workplace is shielded from the public and they generally lack co-workers. The world of work is transforming in respect to demographic, socio-economic and environmental and the demand for domestic work is increasing, which remains mostly invisible, not recognized and undervalued. If these issues are not properly addressed, it will create a severe and unsustainable care work crisis and further increase gender inequalities in the area of work.

Domestic workers make significant contributions to the functioning of households and labor markets. They are often excluded from social and labor protection and face serious decent work deficits. In general, domestic workers perform more than one or multiple of these activities in their workplace[3].

Legal Aspect

The labor rights of domestic workers has been derived from the Constitution of Nepal, 2015. There is Labor Act, 2017 which has specially included domestic work as a specific type of industries and services. Also, there is Labor Rules, 2018, State Civil Code, 2017, Contribution based social Security Act Nepal, 2017 and other legislations which have also defined some rights to the domestic workers. Above all, the Labor Act, 2017 has specifically provided that the rights of the domestic workers shall be determined as prescribed. So, new guidelines or policies are yet to be made specifically addressing the rights of domestic workers.

Situation of Domestic workers during COVID-19

After the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, it has affected all aspects of human life including the world of work. The pandemic is affecting disproportionately - the domestic workers are among the worst hit. For them, the crisis has limited their ability to access their places of work. It is estimated that Nepal has at least 200,000 domestic workers[4] and majority of them are female. The domestic work is typically undertaken by these workers in workplaces that are privatized and informal in nature generally with no work contracts, very low wages, and excessively long hours.

Domestic workers have suffered various impacts resulting from the pandemic, one of the main consequences of COVID-19 has been reduction of employers consequently reducing the working hours and, in some cases, a loss of jobs, resulting from fear and restricted mobility associated with confinement measures of lockdown.[5] Still, some of the employers have said that they will call the domestic worker again to resume their work, once the situation gets better but it is not sure. In the situation of pandemic, the employers are viewing their domestic workers as virus carriers as many of them work at different houses and have to come into contact with many people.

Likewise, the situation has differently affected the groups of domestic workers; for instance, for those registered with recruitment agencies have lesser issues. Similarly, live-in and live-out domestic workers are facing differentiated but exacerbated impacts. For live-in domestic workers, there has been an increase in workload by many folds. Since all the members of the family they work for are at home the whole time. As a result, additional time is consumed during the same household works, i.e cooking, cleaning, washing and care taking which has increased their working hours. This has impacted their wellbeing as they have very few hours for proper rest. On the other hand, for live-out domestic workers, due to lockdown there is no availability of public transportation to the workplace on their regular route to continue their work and earn a living. In some cases, both live-in and live-out domestic workers have continued working during the lockdown too but they have not received their wages on time.

Job security has been a great concern for all domestic workers since they do not have formal agreement with the employers. Nevertheless, there are very few percentages of domestic workers who got employed through recruitment agencies, do have contracts with determined provisions on work hours, pay scale and decent working environment. However, they do not comprehensively address all the necessary requirements of labor law, let alone the requirement for emergency situations like COVID-19.

With a lost or reduced source of income, most of the domestic workers are in economic crisis; which has reduced their capacity to manage daily food expenses and provide education and health services to their family. Most of them are facing shortage of food for daily consumption as they do not have consistency on saving the money for future use. Similarly, they have not been able to afford education and health for their children in a changing context. To curb or cope up with this situation of COVID-19, the local government and civil society organizations have been distributing the immediate relief to the people of their respective areas but in context of domestic workers, it has been reported that some of them have not received any of such support. In case of the receipt of relief packages, it is only sufficient to meet daily food requirements of their family for a few days, repeating the food crisis in the family after a short duration.

Lack of Code of Conduct

Domestic work is not recognized as a work and domestic workers are not considered as a worker and in such context it is hard to make both employer and employee abide by some rules and regulation. Several times domestic work is managed in a very informal manner and conducted in ad hoc basis resulting in several labour rights and human rights violations. It is very important to lay out some basic rules consisting of the rights and duties/ do’s and don’ts of employers and employees to make domestic work more visible and to ensure decent working conditions in this sector of work. The set of code of conduct for both the parties associated with this sector of work will make it clear as what to expect and what to do/not to do for both employees and employer. This will help to ensure rights and duties of both the parties and will be on the same page during the work period.

Transformative policies and recognizing their work as decent work are fundamentals for ensuring a work based on social justice and promoting gender equality for all.

Objectives of the Consultation

Program Design

The consultation shall involve the participation of the representatives from the concerned government Ministries, civil society organizations, Domestic Workers Association, Placement agencies, International Domestic Workers Federation and Trade Unions. The program shall be conducted on the following design:

Expected outcomes of the program

Program agenda: 30th September 2020, Wednesday

|

Time |

Program Agenda |

Presenter |

Remarks

|

|

2:00-2:15 |

Opening, welcome, and objective sharing of the national consultation by WOREC |

Chadani Rana, Secretary, WOREC |

|

|

2:15-2:30 |

Presentation of the existing laws, practices and gap of live-in domestic workers, live-out domestic workers and also the women workers who are engaged in multiple sectors. |

Binita Pandey (WOREC) |

|

|

2:30-2:45 |

Presentation on the importance of ratification of ILO C189, ILO C190 |

Shristi Kolakshyapati (WOREC) |

|

|

2:45-3:05 |

Speakers: Two Domestic workers (10 min each) |

|

They will talk about what should be included in the code of conduct and standard contract of domestic workers. |

|

3:05-3:15 |

Speaker from the Placement agency |

Prasant Dongol |

|

|

3:15- 3:25 |

Speakers from the Employers |

|

They will talk about what should be included in the code of conduct of Employer |

|

3:25-3:30 |

Speaker from IDWF |

Gyanu KC |

|

|

3:30- 3:45 |

Open floor discussion |

Q and A |

|

|

3:45-4:00 |

Remarks from Ministries |

National Women Commission (TBC) National Human Rights Commission (TBC) Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (TBC) Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs (TBC) Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens (TBC)

|

|

|

4:00-4:15 |

Summarization of the consultation and Closing Remarks |

Lubha Raj Neupane, Executive Director, WOREC |

|

|

Moderator: Sandhay Sitoula, ILO Nepal |

|||

List of participants in the consultation:

Government Stakeholders

UN Agencies

INGOs

Embassies

NGOs

Trade Union (Women Workers from the Union)

[5]https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_747961.pdf